Epistemic status: highly speculative / not my area of expertise / writing down thoughts from a silent hike in the nature over the weekend.

Intelligence /ɪnˈtɛlɪdʒ(ə)ns/ — the ability to acquire and apply knowledge and skills.

Consciousness /ˈkän(t)-shəs-nəs/ — the quality or state of being aware especially of something within oneself.

Emotion /ɪˈməʊʃ(ə)n/ — instinctive or intuitive feeling as distinguished from reasoning or knowledge.

In the last years, the field of Artificial Intelligence Alignment has been somewhat preoccupied with the problem of an exponential AGI takeoff, whereas we succeed in building a fairly dumb but general enough artificial intelligence, which becomes conscious. At that point, it’s a matter of scale until that AI becomes a super-smart conscious agent, with its own objectives and motivations, that don’t necessarily align with ours, ushering in the end of humanity. One thing this argument seems to be taking for granted is that the necessary requirement for consciousness to appear — is for the entity to have a sufficiently general intelligence. This is also part of the argument put forward by Giulio Tononi in his Information Integration Theory: if you have a system that integrates information sufficiently well (measured by a value Giulio calls Ф), the system becomes conscious. The larger the measure Ф for a system, the more conscious it is (see this post by Scott Aaronson on some issues he finds with that theory).

Could it be that we’re getting this wrong?

All of the empirical evidence tells us that only conscious, autonomous beings, with their own motivations can develop intelligence. At least that’s all the kinds we’ve seen. Can it be that this is the first time our planet is close to seeing intelligent beings that are not in fact conscious (AKA Philosophical Zombies)?

Intelligence by itself is not enough to create sentient beings

In a somewhat recent podcast discussion, Jeff Hawkins was trying to convey this idea to Sam Harris, who — along with other folks like Elon Musk — is one of the big proponents of taking the exponential takeoff scenario very seriously. I found Jeff’s argument very compelling, although he argues for something much stronger than what I’m about to describe.

We’re getting really close to building general artificial intelligence. Advances in multi-modal learning (like CLIP, for example), as well as self-supervised learning are very promising. In fact, the description of universal learning blocks that comprises our neocortex, according to Jeff, is eerily similar (at least in abstract) to the currently trending deeplearning architecture called “transformers”: it seems to be a basic building block that, when combined in sufficient numbers, can learn all kinds of things — whether those things are visual, auditory, texts, etc. It also seems to be incredible at scaling up: OpenAI has not been able to get to the point where larger transformer-based models started producing diminishing returns as they scaled up.

The argument is — intelligence by itself is lacking the objective function: it doesn’t have its own drives and motivations, and they won’t magically appear if we add more intelligence to the system (for whatever definition of “more” that can be applied to intelligence). The part of the mind that creates and updates the objective function is not the same part that births intelligence — it comes from elsewhere.

For example, as I’m writing this, I’m watching my cat chasing flies outside. Her consciousness (or some other part of her) generates an objective function to not be hungry. Her intelligence interprets those signals in various ways — currently it figures that hunting a fly is a good way to fulfil the objective function provided by the consciousness.

When a chimpanzee feels the need to display social dominance, its intelligence makes it pound its chest or pick up a large stick. When a human feels the need to display social dominance, its intelligence makes it e.g. apply for a PhD programme. The internal motivations are the same, but the extra intelligence in humans makes them come up with smarter and better systems to fulfil the same objective function.

The argument then boils down to the following: building more intelligent entities than we are will not make them sentient. It will just make us better at finding new original and smart ways to fulfil our objective function. In a way, building AGI is a similar event to humans developing the neocortex. AGI is the neo-neocortex.

Note that this does not prevent Fantasia-like situations from happening. If you don’t know what Fantasia is (see the image at the top of this post), you might recognise its close cousin — the paperclip maximiser thought experiment.

The amateur hypothesis of creating sentient beings

So what is missing then? Here’s my absolutely-no-evidence amateur theory for what needs to happen for us to actually create sentient beings (which we might actually not want to do), but also to attain good alignment with our neo-neocortex so as to prevent the Fantasia/paperclip-maximiser scenarios (which we definitely have to do if we want to survive the advent of AGI).

I’m going to readily admit that I have no idea where and how the motivations originate. Since this is so mysterious (to me, at least), and because consciousness seems just as mysterious (to everyone), I am going to just chuck it into the consciousness bucket.

Amateur mind conjecture #1: consciousness generates the objective functions that are then interpreted by the intelligence to produce actions.

How do we not end up trapped in paperclip-maximiser scenarios in our daily lives? Firstly, I believe that we actually do. Addictions, PTSD, phantom pains — all of these seem to be examples of our intelligent (although not necessarily consciously so) parts of the brains optimising the objective function that they should not be optimising. That said, with the exception of some addictive substances and traumatic experiences, we’re great at adjusting our objective functions when they don’t suite us anymore. How do we do that? I my opinion, the answer is — emotions and feelings.

Amateur mind conjecture #2: we align the objective function generated by the consciousness to our values using emotions and feelings.

Here’s an example of how this might work in practice:

You’re pursuing a PhD. As part of that, you get an urge to plagiarise some research.

You do it (or more likely — imagine doing it), you get an emotional response to the result (or an imagined result). It likely makes you feel bad about yourself. You adjust your objective function.

It is worth noting that you don’t actually get to see your objective function. You think your objective function is to get that PhD. But when evaluating plagiarising someone else’s work, you realise that your actual objective function is much closer to something like “produce novel research results in my field”. You get to the more precise definition by having an emotional reaction to an unacceptable (to you) path towards your objective function. Emotions and feelings are sort of like guardrails that don’t let our intelligence pursue any possible way to attain the objective function it has received from our consciousness. This framework also explains the behaviour of psychopaths: they don’t feel certain emotions, therefore some paths to achieve their objective functions are emotionally open to them while those same paths are normally considered taboo.

This also describes the paperclip-maximiser/Fantasia scenarios very well — a psychopathic artificial intelligence is optimising an objective function it has received at any price, without regard for anything that stands in its way. To avoid these kinds of scenarios then, we will have to figure out how to build an interface for realtime updates to the objective functions that our AGIs receive. We plug this new interface into what Stuart Russell describes in his book “Human Compatible” as machine’s uncertainty about the human values. One last thing to note about this is — since we don’t get to see our own objective functions, this interface will likely have to be able to measure our emotions and feelings (e.g. through micro-expressions) in real time, and pass it over to the AGI.

What is missing

With all of this in mind, what’s missing for us to be able to create conscious creatures are:

The seat of motivation/objective function generation. This might be synonymous with consciousness, but might also be a completely different thing. Either way, this is likely the one thing we do not want to build into a machine without a good reason.

An interface that specifies and fine-tunes the objective function to the intelligence, so it can act on it. We know this interface as emotions and feelings. To avoid some of the scary AI scenarios, we’ll want to build this interface — whether it will look like emotions or not.

And coming back to the stronger claim that Jeff Hawkins makes about AI today — what we have is not intelligent by a long shot, so we’d have to get there as well. That said, this is probably the area we’ve made most progress in so far.

Amateur mind conjecture #3: building an artificial general intelligence is not a sufficient enough criteria for the entities to be aware and conscious agents in the world.

What is next

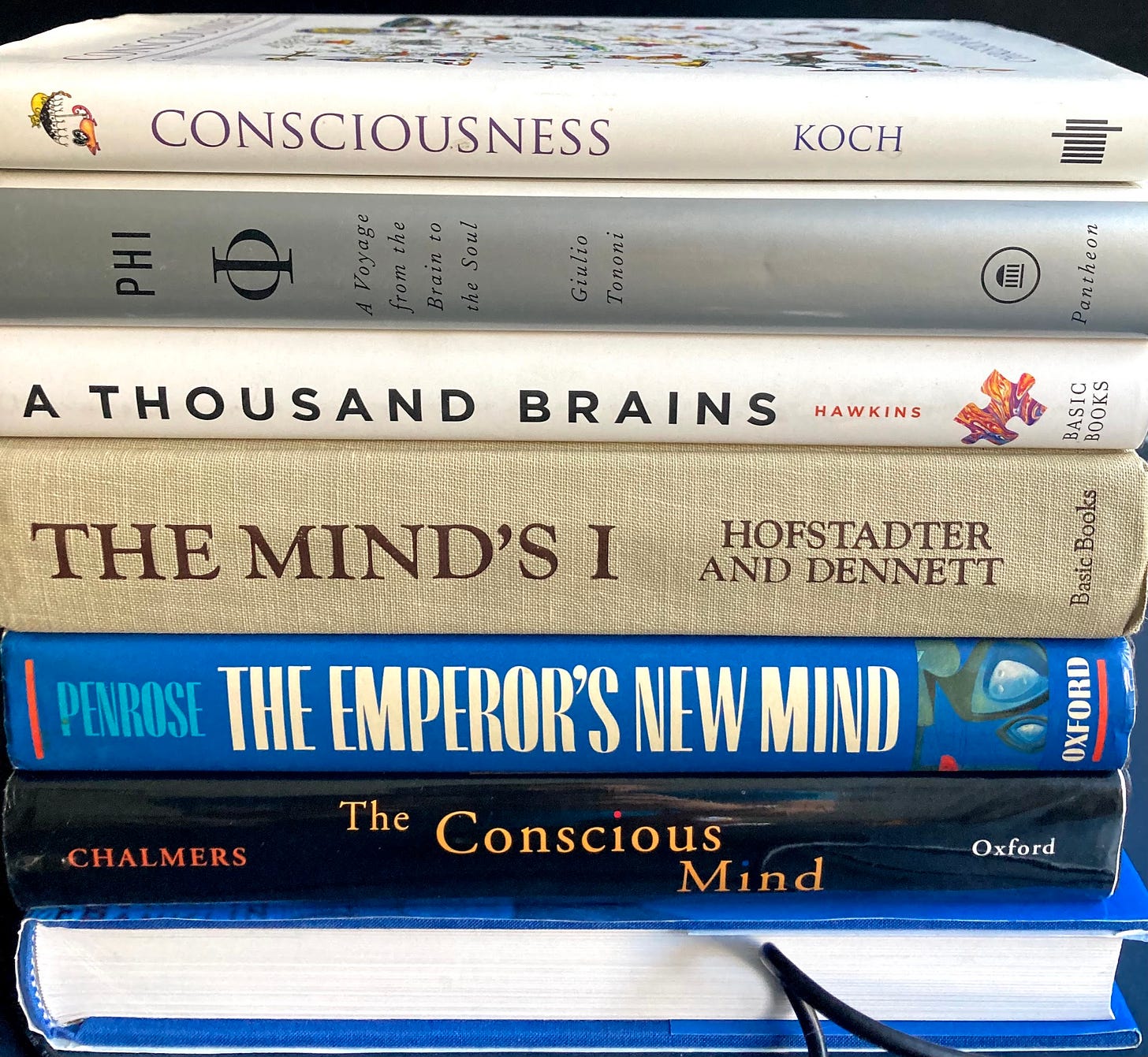

The above are just my semi-structured musings from a week of hiking in the Scottish Highlands and thinking about this stuff. Obviously there are much smarter people who’ve thought much more about every possible bit of this. There’s Giulio Tononi with his Ф; there’s Scott Aaronson with his Q’ approach to hard problems (related to this particular topic is his paper “Ghost in the Quantum Turing Machine”); there’s Roger Penrose with his Quantum Consciousness; there’s Donald Hoffman and panpsychism; there are Hofstadter, and Dennett, and Koch, and Chalmers, and Hawkins, and Harris.

Next steps for me to start wrapping my head around this more includes absorbing some of the literature on the topic. I’ve emptied my reading queue, and have populated it just with the mind/consciousness/intelligence-related books below: